系列综述——微管生长动力学及其数值模拟 Day 6

2016年04月18日 微管 综述 科学 学术 思 添加评论上接Day 5。

本系列章节、图表、引文均连续编号。

3. 微管动态特性的研究现状

微管的动态性质对于微管行使自身的功能至关重要 (85-87)。尽管一系列有形和无形的因素,如化合物和细胞内信号,会调控微管的动态行为 (88),帮助其变形,集束,运动等,有两类动态特性却是微管内秉的,可以在纯净的微管蛋白溶液中发生:一为踏车现象,另一为动态不稳定。由于微管主体是紧实的晶格结构,一般认为亚基的添加和移除只能通过端部发生,以上两种动态行为就均与微管端部的加、解聚相关。

环境中亚基的浓度会影响微管的组装,如果高于临界浓度则微管倾向于加聚,反之则解聚。微管的极性结构导致正端有着比负端更强的动态性,两端的临界浓度不同,若周围环境恰好使正端加聚而负端解聚,且两者速率相等,则表面上看,微管的长度并没有发生变化,亚基仿佛从正端流向了负端,这就是踏车现象 (89-93)。踏车并不需要任何的外在驱动,另一细胞骨架纤维——肌动蛋白丝也发生踏车。

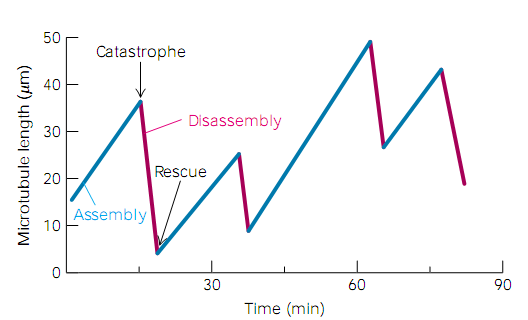

动态不稳定性是指微管不停地在生长和收缩间随机地转换,长度不断发生着变化 (94-96),如图11所示 (2),从加聚状态突然转为解聚状态称为“灾变”,而从解聚转为加聚则称为“拯救”。“灾变”和“拯救”的发生都是随机的,一般可以用四个参数来刻画动态不稳定性的平均过程——生长速率,收缩速率,灾变频率,和拯救频率。这几个参数间是解耦的,即使一根微管上非常频繁地发生着灾变,其依然可以生长地很快。值得注意的是,虽然快速的动态行为对许多细胞至关重要,比如有丝分裂中期就是依靠微管的不断伸长和收缩来捕获染色体,但在一些不能复制的细胞,如神经元中,微管却是基本保持静止的,此时结构如果去组装将导致神经变性,引发阿兹海默症等疾病;在这些情况下,微管的稳定是重中之重。

微管的正端和负端都能体现出动态不稳定性,不过它们的生长和收缩速率、灾变和拯救频率各不相同 (96)。一般的,正端生长更快,灾变也更频繁 (13);在体内,则两端的动态性差别更显著,负端在一些结合蛋白的作用下基本保持稳定 (97)。大多数动态不稳定性的研究都着眼于正端。

参考文献:

(2) Berk, A., Matsudaira, P., Kaiser, C. A., Krieger, M., Scott, M. P., Zipursky, L., and Darnell, J. (2003) Molecular cell biology, 5th ed., W. H. Freeman.c

(13) Tran, P. T., Walker, R. A., and Salmon, E. D. (1997) A metastable intermediate state of microtubule dynamic instability that differs significantly between plus and minus ends, Journal of Cell Biology 138, 105-117.

(85) Desai, A., and Mitchison, T. J. (1997) Microtubule polymerization dynamics, Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 13, 83-117.

(86) Inoue, S., and Salmon, E. D. (1995) Force generation by microtubule assembly disassembly in mitosis and related movements, Molecular Biology of the Cell 6, 1619-1640.

(87) Hyman, A. A., and Karsenti, E. (1996) Morphogenetic properties of microtubules and mitotic spindle assembly, Cell 84, 401-410.

(88) Heald, R., and Nogales, E. (2002) Microtubule dynamics, Journal of Cell Science 115, 3-4.

(89) Galjart, N. (2005) Clips and clasps and cellular dynamics, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 6, 487-498.

(90) Margolis, R. L., and Wilson, L. (1978) Opposite end assembly and disassembly of microtubules at steady state in vitro, Cell 13, 1-8.

(91) Margolis, R. L., and Wilson, L. (1998) Microtubule treadmilling: what goes around comes around, BioEssays 20, 830-836.

(92) Panda, D., Miller, H. P., and Wilson, L. (1999) Rapid treadmilling of brain microtubules free of microtubule-associated proteins in vitro and its suppression by tau, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96, 12459-12464.

(93) Rodionov, V. I., and Borisy, G. G. (1997) Microtubule Treadmilling in Vivo, Science 275, 215-218.

(94) Mitchison, T., and Kirschner, M. (1984) Dynamic instability of microtubule growth, Nature 312, 237-242.

(95) Belmont, L. D., Hyman, A. A., Sawin, K. E., and Mitchison, T. J. (1990) Real-time visualization of cell-cycle dependent changes in microtubule dynamics in cytoplasmic extracts, Cell 62, 579-589.

(96) Walker, R. A., Obrien, E. T., Pryer, N. K., Soboeiro, M. F., Voter, W. A., Erickson, H. P., and Salmon, E. D. (1988) Dynamic instability of individual microtubules analyzed by video light-microscopy - rate constants and transition frequencies, Journal of Cell Biology 107, 1437-1448.

(97) Goodwin, S. S., and Vale, R. D. (2010) Patronin Regulates the Microtubule Network by Protecting Microtubule Minus Ends, Cell 143, 263-274.